Where Does Columbia River Start

Description

The Columbia River, quaternary-largest by volume in Due north America (annual average of 192 meg acre-feet at the oral cavity) begins at Columbia Lake in the Rocky Mountain Trench of southeastern British Columbia at about 2,656 anxiety in a higher place ocean level. The geographic coordinates at the head of the lake are 50°13' due north latitude, 115°51 due west longitude.

The river flows north for some 200 miles (322 kilometers) and so turns south and flows for about 270 miles (434 kilometers) before crossing the border into Washington at River Mile 749, that is, 749 miles (1,205 kilometers) inland from the Pacific Ocean. More precisely, according to the BC Freshwater Atlas, the Columbia River in British Columbia is 760.356 kilometers long (472.463 miles).

For its get-go approximately 150 miles (241 kilometers) in the United States, the Columbia forms the reservoir behind 1000 Coulee Dam. The river then bends west, south and east through central Washington, turns southward and then west, and forms the border between Oregon and Washington to the Pacific Ocean. The mouth of the river is about 10 miles (sixteen kilometers) west of Astoria, Oregon. The geographic coordinates at the mouth (near Greatcoat Disappointment, Washington) are 124.09344 west longitude, 46.246922 north latitude (these are the coordinates the U.S. Ground forces Corps of Engineers cites as River Mile Zilch). The total length of the river is nearly i,243 miles (about 2,000 kilometers). The drainage basin covers 259,000 square miles (670,810 square kilometers), approximately the size of France, drains portions of seven states and British Columbia, and covers three degrees of latitude and ix degrees of longitude.

The Columbia mainstem has numerous tributaries, big and small. The biggest of these, in terms of length and book, are: longest:

- Snake (one,078 miles)

- Kootenai/y (485 miles)

- Deschutes (252 miles)

- Yakima (214 miles)

- Willamette (187 miles)

The largest by average annual belch book:

- Snake (54,830 cubic feet per 2nd (cfs) at Ice Harbor Dam)

- Willamette (33,010 cfs at the Morrison Bridge in downtown Portland)

- Kootenay/i (27,616 cfs at Cora Linn Dam near Nelson, British Columbia)

- Pend Oreille (26,320 cfs at Box Canyon Dam in northern Washington)

Afterwards that, other tributaries are all under 10,000 cfs annually.

Considering of its unique situation close to the bounding main and laced with tall mount ranges, the Columbia evolved equally one of the great rivers of the earth in terms of its runoff and the diverseness of its habitat. From its headwaters to its mouth, the river drops steadily at a rate of about two feet per mile, and virtually of its course is through rock-walled canyons. Down these rocky canyons the Columbia pours biggy volumes of h2o, emptying an annual average of 192 million acre-feet into the Pacific; much of its volume originates in its middle and upper reaches. The Canadian portion of the bowl, for example, contributes almost 20 percent of the river's total volume (this includes the water from rivers that brainstorm or pass through the United States before entering the Columbia in Canada, such as the Clark Fork/Pend Oreille system and the Kootenay, which is spelled Kootenai in the United states).

The combination of loftier volume and stable canyons made the Columbia an ideal hydropower river. Today there are xiv dams on the mainstem Columbia, outset with Bonneville at river mile 146 and ending with Mica at river mile 1,018, and more 450 dams throughout the basin. Dams on the Columbia and its major tributaries, primarily the Snake River, at approximately 1,078 miles its longest feeder stream, produce half of the electricity consumed in the Pacific Northwest. The Columbia River dams inundated many of the river'due south dangerous rapids, well-described and named past early settlers and travelers on the river for their often treacherous passage — Dalles des Morts (Expiry Rapids), Hell Gate, White Cap, Rock Slide, Boulder, Surprise.

The huge volume of h2o pouring to the ocean, most of it during the jump and early summer when the snowpack melts, likewise produced ideal environmental conditions for cold-water fish, particularly anadromous fish like salmon and steelhead. Other anadromous species in the Columbia include lamprey, sturgeon and shad. But salmon and steelhead are the river's legacy fish. Betwixt 10 1000000 and 16 million salmon and steelhead are believed to have returned to the river to spawn annually prior to the 1840s, when clearing to the Northwest began to accelerate and pressures on fish, through harvest and habitat destruction, for instance, began to take a price on the runs. Through the twentyth century, the number declined to less than 1 million, but the returns began to rebound in the late 1990s, a time when conservation efforts were increasing in freshwater habitat and ocean feeding atmospheric condition were improving.

Creation

There was a beginning of the Columbia, simply as there is a get-go of all things. In 1 tradition, the beginning is told in myth. In another tradition, the story is one of geology. The mythic could be said to inform the geologic. They are not so unlike.

Co-ordinate to a Yakama legend, the mythical Columbia began, as does the creation story in Genesis, with h2o. In Genesis, the Earth was formless and empty, and the Spirit of God, the creative strength of the Universe, hovered over the water. In the Yakama legend, the hovering spirit, Whee-me-me-ow-ah, the Cracking Chief Above the Water, reached down from the heaven where he lived and scooped handfuls of mud from the shallow places and made the land. Some of the mud he piled high to make mountains, and some of it he made into rocks. He fabricated trees and roots and berries grow on the country, and he made human from a ball of mud. He gave the human being instructions well-nigh hunting and fishing, and when the man became alone the Great Chief Above fabricated woman and taught her how to assemble and prepare berries, and melt the salmon and game the man brought to her. He blew his breath upon her and made her skilled in these things so that she could teach her daughters and granddaughters.

Coteeakun, an associate of Smohalla, the great Yakama prophet, told this version of the creation to Major J.W. MacMurray of the U.Southward. Army when he was stationed among the Yakama in 1884-85, according to author Ella Clark. It may be an authentic retelling of a story handed down through generations, or with its distinctly Biblical tone information technology may be influenced by the work of Christian missionaries of the time. Other Northwest tribes take similar oral traditions about the cosmos of the world, commonly involving a benevolent Principal Higher up and the creation of distinct levels — underworld, earth and sky — linked through the middle in some manner, as past a pole, a tree or a waterfall. Humans too were divinely created by the Chief Above or, in some traditions, by his agent Coyote.

The Columbia itself was the work of Coyote in most oral traditions. Realizing that salmon were in the body of water and that people in the interior needed food, Coyote fought a battle with the behemothic beaver god Wishpoosh, bankroll him through the Cascade Mountains to the ocean and so killing him. It was the back-and-forth slashing action of the great beaver's tale that scraped out the Columbia River Gorge and opened the channel to the sea. This made salmon bachelor to the people. Coyote cut the beaver to pieces and distributed the pieces on the land, and they became humans. Later, Coyote tricked the five consume sisters, who had built a dam across the river to block salmon, into leaving him lone there. While the sisters were away, he destroyed the dam, once more freeing the manner for salmon. The rocks of Celilo Falls were the remnants of the dam.

Thus nosotros have the Columbia River and salmon. In that location are other legends about the origin of the river and its people, legends that also coincide with the geology and environmental of the river as we know it today. In that location were cataclysms of volcanism, floods and earthquakes. The start humans to live what is now the Northwest migrated here between 12,000 and 30,000 years ago in two waves, ane from Asia around the northern rim of the Pacific Ocean and another from northern Europe, to settle along the Columbia, and places further south.

Much, much earlier, the ancient Columbia evolved about 17 million years ago, according to accustomed geologic history. Before that, the geologic record is hard to read and open to interpretation. But at any rate, the ancient Columbia was a lot different from the river we know today. The course of the aboriginal river formed following repeated floods of basalt upwelling from the depths and spreading across what is now primal Washington and Oregon, and western Idaho and Montana, flowing toward the center of a smashing depression caused past the sheer weight of some 90,000 cubic miles of basalt, layered in more than 200 separate flows. Repeated basalt flows formed the area nosotros know today as the Columbia Plateau of central Washington and Oregon. The dandy depression caused an inward slope from perimeter elevations of 2,000 to iv,000 anxiety above ocean level to less than 500 feet in the Pasco Basin of south central Washington. The river, which began so every bit it begins at present, in British Columbia, followed, finding its manner to the sea through what is now the Columbia River Gorge of the Cascade Mountains.

Beginning nearly 12 million years agone, the pressure began to warp the bowl into the feature east-west folds that are the modernistic-24-hour interval tributary river basins. Information technology is something of an irony that the rich farmland of the Columbia Plateau, known equally the Palouse Germination, resulted from extremely arid weather between the advance and retreat of glaciers during the last Ice Age. During the interglacial warm periods, winds deposited glacial dust and silt up to 150 anxiety deep in some places.

Toward the terminate of the last Water ice Age, 12,000 to 15,000 years ago, a series of catastrophic floods, maybe the greatest floods ever in the history of the world, scoured the route of the Columbia through what is at present Washington and the Columbia River Gorge. These floods, caused by the repeated failure of an ice dam at the outlet of Glacial Lake Missoula, did not change the route of the Columbia, but did scour its aqueduct, and much of eastern Washington, down to the basalt layers and left the river with a stone-solid channel, in some places deep and steep-walled, laced with dramatic waterfalls.

Geology and mythology need not be mutually exclusive. Neither tradition needs to exist more right than the other. What is important is the river had a first, and that in the beginning, before everything else, in that location was water.

Discovery of the Columbia

In the 16th century, somewhere in what is now the American Southwest, in the mists of imagination and the estrus of the desert, lay seven cities of legendary wealth. These were unimaginably rich with turquoise, argent, gold, and furs, or so the Spanish conquistadors believed every bit they plundered, proselytized and steadily pushed deeper into the wilderness. By land and by sea, Spaniards pushed west and northward across the land they called New Spain — present-twenty-four hour period Mexico — searching for the fabulous wealth.

Some 60 years later the first Spanish colonies were established in New Spain, Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth, England, on Dec. 13, 1577, with 100 men and three ships: the Pelican, Elizabeth, and Marigold. Officially, he planned to explore "Terra Australis Incognita," the Unknown Land of Australia, as a possible site for colonization. He also planned to search for the western entrance to the Northwest Passage. Privately, he had Queen Elizabeth's permission to loot any Spanish ships he might encounter.

Storms in the Strait of Magellan sank the Marigold and forced the Elizabeth to plow for home. Drake continued in the Pelican, which he renamed the Golden Hind. In 1579, having traveled half way around the world, and later robbing a number of Spanish ships to the point that his own Golden Hind was heavily burdened with stolen gold and argent, precious gems and jewelry, Drake sailed n along the Pacific coast. On June iii, the Golden Hindis believed to have reached at least 42 degrees northward breadth (northern California) and perhaps as far as 48-50 degrees (northern Washington or Vancouver Island). He turned back and plant a harbor, probably only n of San Francisco Bay, where he landed to repair his ship and take on water and food earlier sailing w beyond the Pacific and abode.

Meanwhile, Spain's quest for gold and territory in the Northwest connected, with the next explorers reaching the present-mean solar day Oregon coast in Jan 1603. Through these early on explorations, the Pacific Northwest began to emerge from the mists of imagination. The Northwest was condign a known place on rough maps, but despite the lure of the imagined Northwest Passage more than 100 years would laissez passer before Spain or whatever other nation would attempt such an exploring voyage once again.

Spain, which had established outposts in what is now Mexico, continued to button north. While Spanish explorers reached the present-day Oregon coast in January 1603, more than a century would pass before Spain or any other nation would sail up the Northwest declension once again.

In July 1775, Bruno Heceta in the Sanitago and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra in the Sonora, left San Blas, a Castilian port on the Pacific Declension a curt distance due north of present-day Puerto Vallarta, searching for the illusive Northwest Passage, envisioned every bit a passage linking the North Atlantic to the Northward Pacific. Off the coast of present-24-hour interval Washington, post-obit a predetermined plan, the two ships parted and conducted separate investigations every bit far north every bit Alaska. On his return journey southward, Heceta discovered a large bay at about 46 degrees north latitude penetrating far inland. It was the Columbia, and he was the beginning European to sight the mouth of the river. He tried to sail into it but was pushed back past the outflow, and with his crew weak from scurvy he was afraid that if they dropped the anchor to wait for more favorable atmospheric condition on the bar, the crew might non be able to lift information technology. He likewise had but one longboat left, have lost another during a skirmish with Indians on the northern coast of Washington, and he feared losing the boat and crew in the turbulent outflow. Then he left for San Blas.

Heceta supposed the Columbia was the passage discovered, or at to the lowest degree attributed, to the Spaniard Juan de Fuca's 1592 voyage. De Fuca'due south strait was said to exist between latitudes 47° and 48°, simply Heceta wrote that he had been there and seen no such strait. Heceta named the two capes at the rima oris of the river -- the northern one San Roque (Cape Disappointment today) and the southern one Cape Frondoso (Cape Adams today). This was the primeval written description of the mouth of the river.

In 1778, Captain James Melt, the famed British explorer who made iii voyages to the Pacific, missed the mouth of the Columbia altogether on his tertiary voyage. Arriving on the Pacific coast after having discovered the Hawaiian Islands, which he named in award of the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, Cook outset sighted land in the vicinity of Newport, Oregon, on the nowadays-day fundamental Oregon coast. He described the land and named Cape Foulweather, a few miles north of Newport, and then, having accurately described the weather in the naming of the rocky headland, was blown out to sea and did non see land again for near two weeks. [Nosotros were] "unprofitably tossed nigh for the last fortnight" he wrote in his journal for March 21, 1778. His instructions for the voyage fabricated clear that he was non to explore any openings, such as the Columbia, if he had seen it, until he reached 65 degrees northward. Similar other explorers earlier him, he was searching for the Northwest Passage to the Atlantic, and information technology was believed to have its western entrance at near that breadth.

Cook followed the coasts of present-day British Columbia and Alaska to the Aleutian Islands and the northern Bering Sea, where he was stopped by water ice. While he did non observe a Northwest Passage, his crew traded for sea otter pelts on the Alaskan declension and later on sold the furs at Canton for a huge turn a profit. Give-and-take of the value of sea otter pelts — they were softer and finer than any other fur at the time — spread fast, and the huge profits were confirmed in the official report of Cook's voyage. Presently British traders in Republic of india and County were outfitting ships for trading expeditions to the Pacific coast, equally were other entrepreneurs in the United States and Europe.

John Meares was the side by side to sight the oral fissure of the Columbia, in July 1788 while on a fur-trading voyage from Nootka Audio. Meares sighted and named Mount Olympus and so coasted due south to take a wait at the large bay and surge of fresh water observed by the Spaniard Heceta in 1775. Meares was a erstwhile British naval officeholder who offset visited the Northwest coast two years earlier on a voyage in search of sea otter pelts. He arrived off the mouth of Heceta'south bay on July five. He attempted to cross the bar, but encountered huge and dangerous breakers, merely like Heceta. Then he stood off, waiting for the ocean to calm and eventually decided there was no river. On July 6, 1788, he named the northern cape Disappointment, a proper name that stands to this twenty-four hour period. He named the bay Charade. He wrote in his journal, "Nosotros can now assert that there is no such river." He arrived back at Nootka on July 26.

Four years later on, he would be proven wrong.

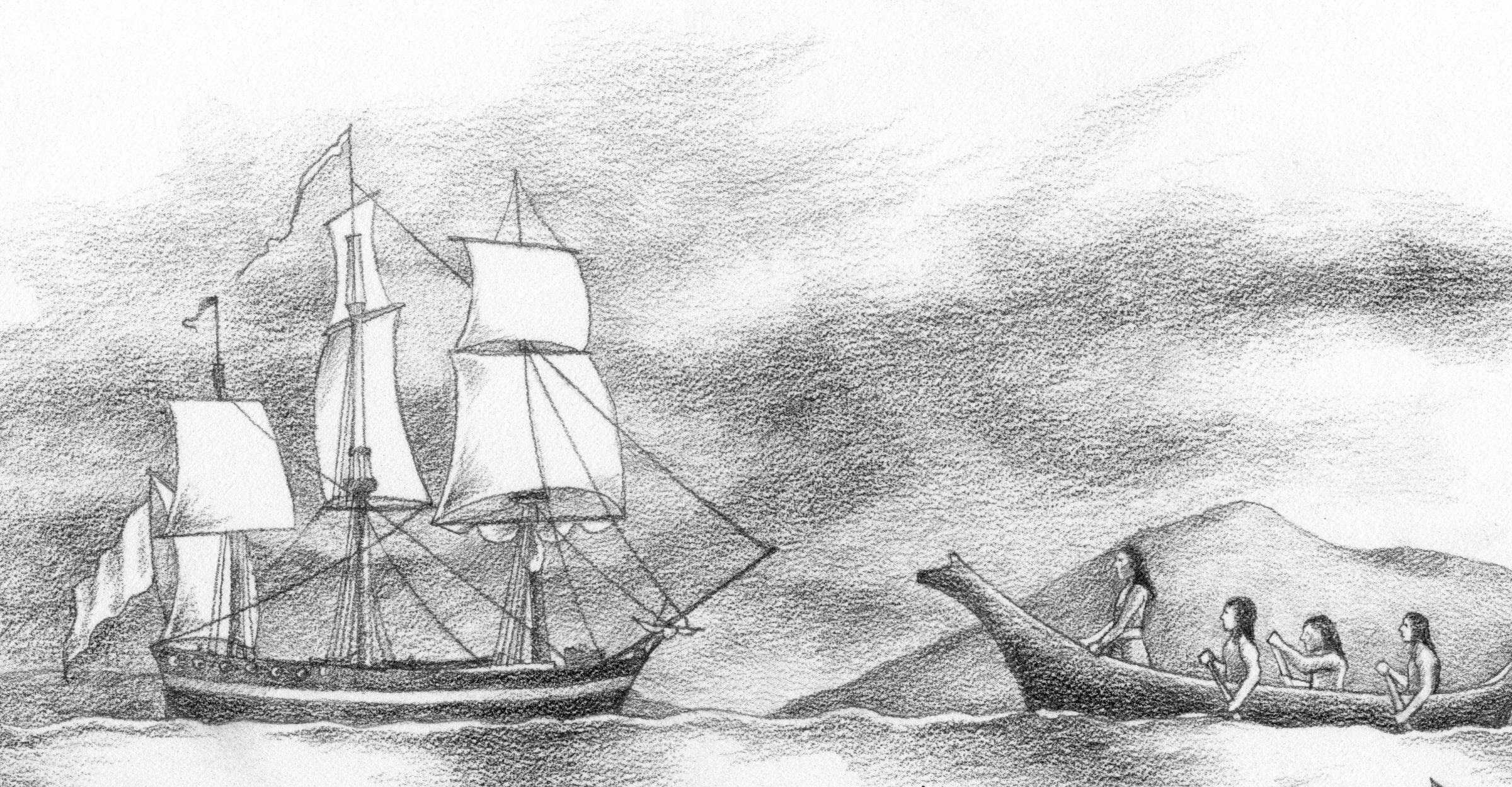

At 4 a.k., April 29, 1792, just inside the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca off the Northwest coast of present-mean solar day Washington, two great bounding main captains had a brief come across that literally changed the grade of Columbia River history. One was an American, fur trader Robert Grayness of Boston, and the other was British, Captain George Vancouver.

Information technology was common practice when ii ships met in remote corners of the earth for the captains to substitution notes, observations and bounding main charts. Grayness and Vancouver had arrived at this point having sailed upwardly the w coast, and both had noticed the rima oris of the Columbia River. But neither had investigated it. Vancouver noted in his log for Apr 27, two days earlier:

On the south side of the promontory was the appearance of an inlet or a pocket-size river, the land behind not indicating it to be of any great extent; nor did information technology seem accessible for vessels of our burthen, as the breakers extended from the above point, two or 3 miles into the ocean, until they joined those on the beach nearly iv leagues farther due south. The Sea had now inverse from its natural, to river-coloured h2o; the likely consequences of some streams falling into the bay, or into the bounding main to the n of information technology, through the low land. Not considering this opening worthy of more than attention, I connected our pursuit to the Due north .W., beingness desirous of embracing the prevailing cakewalk.

A seaman on the Chatham, a tender to Vancouver'south send, the Discovery, too saw the mouth of the Columbia and subsequently wrote in his own journal:

The Discovery made signal we were standing into danger and nosotros hauled out; this state of affairs is off Cape Disappointment from whence a very extensive shoal stretches out and there was every advent of an opening actually seen, but it was passed without appreciating the importance of the identify.

It may non have been so much that Vancouver did not capeesh the importance of the place but that he considered the opening too small or dangerous, and to investigate would take violated his specific orders. He had ii master tasks. One was to receive restitution from Kingdom of spain for the land and buildings at Nootka on what is at present Vancouver Island. British possessions in that location had been seized past Kingdom of spain in 1789. The other, and more important job, was to search the Pacific coast as far north as 60 degrees for the opening of a Northwest Passage, and he was advised confronting pursuing "any inlet or river further than it shall appear to be navigable by vessels of such burden as might safely navigate the Pacific Ocean." Vancouver considered the Discovery too large for what he perceived equally a shallow and dangerous opening to a supposed river.

Off Greatcoat Flattery, Vancouver sent Lt. Peter Puget and the send'due south botanist, Archibald Menzies, to interview Grey. Afterwards they brought back their study, Vancouver wrote:

The river Mr. Grayness mentioned should from the breadth he assigned to information technology, take existence in the bay southward of Cape Thwarting. This we passed on the morning of the 27th; and as I then observed, if any inlet should be found, it will be a very intricate ane, and inaccessible to vessels of our burthen, owing to the reefs and broken water which appeared in its neighborhood. Mr. Gray stated that he had been several days attempting to enter it, which he at length was unable to effect in outcome of a very potent start ... I was thoroughly convinced, as were besides nigh persons on lath that we could not possibly have passed any condom navigable opening, harbor or identify of security for aircraft on the coast, from Greatcoat Mendocino to Classet ... nor had nosotros any reason to alter our opinions.

Vancouver went on to the east to investigate the extent of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, following in the path of Spanish explorers who had been in the expanse for the past 2 years. Vancouver would go farther, however, and exist the first to explore Puget Sound, which he would name for one of his lieutenants. Greyness went west and south along the coast to have another expect at the openings he had observed earlier, including the one that now bears his name, Gray's Harbor, and the Columbia. On May 11, Grey discovered the Columbia, noting in his ship's log for that day:

At iv A.M. saw the entrance of our desired port. … When we were over the bar, we constitute this to be a large river of fresh water, upwardly which we steered. At one, P.One thousand., came to with the small bower, in 10 fathoms, black and white sand. … Vast numbers of natives came alongside. … So ends.

Grey anchored one-half mile off the due north shore of the estuary between modern-solar day Point Ellice and McGowan's Station. Thus the Columbia became — and remains — an American river. The American authorities was well aware of Grey's expedition. He carried an official letter of introduction from the president, George Washington. But equally easily, the Columbia could have been British, but kickoff Meares and and then Vancouver insisted it was either nonexistent or insignificant.

These were well-accomplished explorers, Vancouver especially so. Why were they then adamant in spite of intriguing bear witness of a great river? The answer might be, in a word, arrogance. Meares simply was convinced he was right. Every bit for Vancouver, Historian Richard Speck suggests that while brilliant and well-experienced as an explorer, Vancouver was a victim of his own "towering pride." Despite the information he gleaned from Gray, Vancouver believed, by his ain observations, that there were no ports or rivers of significance betwixt Mendocino and Cape Flattery. Speck suggests that Vancouver, as a British naval officer, likewise probably was quite right to disregard the information of a "Yankee tramp trader" about the mouth of the Columbia. If Vancouver can be criticized, Speck suggests, information technology would be for his refusal to mind the obvious signs of a corking river — discolored ocean water, floating debris, a potent current pushing out to sea. Regardless, he effectively threw abroad the discovery by which Dandy Britain could have claimed all of Old Oregon. If not for this, the country of Washington north of the Columbia River might be part of Canada today.

A more sympathetic explanation of why Vancouver dismissed the oral fissure of the Columbia is provided by British Columbia historian Barry Gough, who believes that the Admiralty urged Vancouver to apply his judgment and be cautious in guild to save fourth dimension and to devote the voyage to the job of discovering the western opening of a Northwest Passage connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Gough writes that in gild to be commercially and strategically useful, the passage had to be large, and to Vancouver the opening of the Columbia did not announced large. As well, Gough suggests, Vancouver may have placed too much confidence in Meares' earlier conclusions.

Gough as well notes that Vancouver was "distressed" that Gray had discovered the river, and that Vancouver later had Lieutenant Broughton of the Chatham survey the river almost 120 miles inland in the hope of extending British claims. That was in Oct 1792, when Vancouver, having been presented a copy of Greyness'south nautical chart of the Columbia by the Castilian commander at Nootka, decided that on his way to the Sandwich Islands, where he planned to spend the winter, he would investigate the river. For two days he looked for a channel safety enough for the Discovery. Finding none, he ordered Broughton, commanding the smaller Chatham, to investigate the river.

Broughton crossed bar on October 19, 1792. Historian Bernard DeVoto writes that while Gray'south chart showed he had gone upriver 36 miles:

… by triangulation, computation and divination Broughton scaled this down to fifteen miles and decided that up to here the river had non narrowed enough to exist chosen anything but a sound. A freshwater sound that opened on the ocean would be unusually interesting geography but it would do to peg downwards an majestic claim.

Broughton anchored the Chatham in the estuary and went on upriver with a crew in the transport's longboat, naming sites including Puget Island and Mount Hood (Vice Admiral Samuel Lord Hood signed the orders for Vancouver's trek). Forth the way, he and his crew traded with Indians for salmon. These included 3 fish acquired at a Chinook village on the 21st.

On October 30 on the shore probably well-nigh present-day Corbett, Oregon, Broughton claimed the river, its watershed and the coast for Great Britain. In short, he claimed for Keen Britain the river Gray had named. Vancouver accepted Broughton's claim, "having every reason to believe that the subjects of no other civilized nation or state had always entered this river before." Vancouver too wrote, "It does not appear that Gray either saw or was ever within five leagues of its [Columbia] entrance."

Some regime suggest the latter quotation was made for diplomatic purposes considering Nifty Britain later used information technology in boundary negotiations with the United States. Speck writes: "[Vancouver] had unhesitatingly laid absurd claims to Spanish lands far south of any reasonable boundary, and now his lieutenant baldly claimed for England a river which had been discovered by another nation." Broughton'south deceit was the ground of Britain'south tenuous merits to the Columbia until the boundary matter finally was addressed, showtime in the Convention of 1818 that established joint possession of the Northwest and ultimately in the Treaty of Oregon, which the 2 countries signed in June 1846. The treaty fixed the border at the 49th parallel.

According Gough, "Vancouver's failure to discover the river plagued British diplomats, who in discussions with their American counterparts were obliged to base their priority of claims on the basis of the earlier, more brief discoveries of Drake and Cook." Historian Glyn Williams writes that the "one serious blemish" on Vancouver'south 1792 expedition to the Pacific Northwest coast was that he failed to sympathise the significance of several major rivers, including the Fraser and Columbia. Nevertheless, Vancouver conducted such a thorough survey of the coastline from the Strait of Juan de Fuca to southeastern Alaska that 100 years later his maps were still in use. "He proved there was no Northwest Passage in these latitudes, but he inadvertently left the Columbia River for others," Williams writes.

There can be no dubiety almost who discovered the Columbia. A record remains intact, notably including Gray'south log and the journal of John Boit, Grey's 5th mate on the Columbia Rediviva, who wrote extensively about the river. In his periodical for May xv, 1792, four days subsequently the Columbia Rediviva crossed the bar, Boit wrote:

Sent the cutter and constitute the main Aqueduct was on the South side, and that there was a sand bank in the middle, as we did non expect to procure whatever Otter furs at whatever distance from the Sea, we contented ourselves in our present situation, which was a very pleasant one. I landed abreast the Ship with Captain Gray to view the Country and take possession, leaving accuse with the 2nd Officer. Found much clear basis, fit for Cultivation, and the forest generally clear from Underbrush.

Boit also wrote glowingly about the abundance of salmon, beavers, nuts, elk and deer in the estuary, and the level, fertile ground. He envisioned a settlement there, and another in the present-day Queen Charlotte Islands that "... wou'd engross the whole trade of the NW coast (with the help a few minor benumbed vessels)."

To this 24-hour interval there is a remnant of the British and American explorations in the names of the two capes at the rima oris of the river. Cape Disappointment on the north side was named in 1788 by John Meares, the British explorer (Gray's "Cape Hancock" did not stick); Point Adams on the south side was named in 1792 by the American, Robert Grey, for John Adams, vice president of the Us who was elected to a 2d term that yr.

Where Does Columbia River Start,

Source: https://www.nwcouncil.org/history/ColumbiaRiver/

Posted by: williamsyestan73.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Where Does Columbia River Start"

Post a Comment